The Birth of the Super Distortion

How DiMarzio Changed the Electric Guitar

Foreword by Eric Kirkland

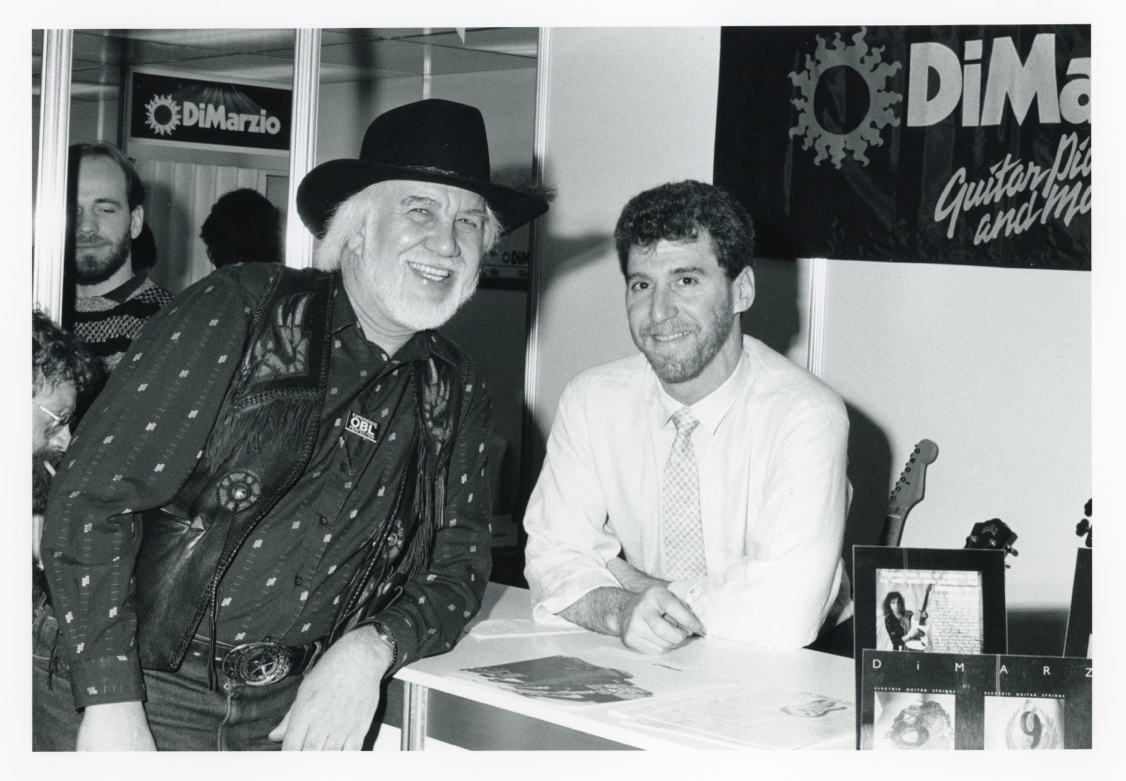

Guitar World magazine may have said it best when they acknowledged and celebrated Larry DiMarzio’s influence on the guitar industry in their May 1994 issue, listing him in the top 100 innovators.

Larry DiMarzio is responsible for the revolutionary idea that a guitarist could take a stock instrument and ‘personalize’ it — customizing its sound to suit their individual taste and playing style.

The invention of replacement pickups gave life and provided significant improvement to the sound of the modern guitar.

The impact of DiMarzio’s drop-in replacement pickups goes far beyond providing players with a powerful new way to shape their sound. DiMarzio’s pickups quite literally made it possible for the next generation of guitar builders to challenge the establishment. The Super Distortion’s story and the musical revolution it helped kick off can’t be told without also telling Larry DiMarzio's story and the origination story of the DiMarzio company.

In plain terms, DiMarzio pickups powered the Ibanez, Hamer, Charvel, BC Rich, Dean, Spector, Jackson, Sadowsky, SD Curly instruments and helped to create a new sound. (And loads of Gibson and Fenders as well!) Fender and Gibson weren’t up to the task and certainly weren’t going to supply their rivals with their pickups. DiMarzio’s fresh and often-radical ideas were a key building block for the guitarists and guitar builders with their eyes to the future. DiMarzio pickups were embraced by a generation of impossibly gifted musicians who used them to redefine the instrument’s technical and sound limits. DiMarzio helped give voice to their sonic expression. And that’s what Larry DiMarzio is still doing today.

“I invented replacement guitar pickups and the Super Distortion®, the world’s first replacement pickup, developed over a period of several years.

Happily, it’s the same as it ever was… built in America by the same people in the same place and not allowed to be watered down by corporate take overs or financial banking groups. DiMarzio is a company that was built on revolution, integrity, art, imagination, and innovation.

Here’s my story…”

Early days

My interest in sound started when my Uncle Jimmy took me to the Brooklyn Academy of Music to see the opera La Traviata. I was six. He was a huge opera fan and it played constantly in his small apartment. I can still remember taking our seats in the opera house, the lights going down, and the music beginning. The sound was so much bigger and better than anything I’d ever heard in a movie theater or from my uncle’s record player. The singing was all in Italian and I couldn’t understand a word so my uncle explained the story, making it even better. On the way home, I whistled the Brindisi (aka “The Drinking Song”), that made him smile and that made me happy.

At thirteen, my mom decided that I should take music lessons and I was given the choice between accordion or guitar. Luckily, I chose the guitar…

At thirteen, my mom decided that I should take music lessons and I was given the choice between accordion or guitar. Luckily, I chose the guitar and for the next year my teacher came to the house, tasked with teaching me “Frère Jacques” and “Jingle Bells” from the Mel Bay song book… a torturous experience for both of us.

My mother and father loved spending summer weekends in Rocky Point, Long Island and bought a house there. To pay the mortgage they rented it year-round and my dad converted the garage into a living space and with a shower, a toilet and kitchen sink.

That summer a professor of physics and his wife from Stonybrook University were living in the main house. They were wonderful people and we got to be friends. They would go to the beach at night and sing folk songs around a campfire and I got to tag along. I quickly realized this was a far better use for my guitar skills than the lessons I was taking. I got a Peter, Paul and Mary song book and was soon playing along with them.

I started Brooklyn Tech that fall and my plan was to study electronics and play guitar with neighborhood bands. One of my early bands even played in a battle of the bands at the Worlds Fair the next summer.

New York Minute

By the summer of 1969, I was spending most of my weekends at the Fillmore East, devouring every type of music that Bill Graham brought to the city or at the Longview Country Club, a bar in the Union Square district of Manhattan.

The Fillmore East was the sister venue for Graham’s west coast show place. There were two shows a night, one at 8:00 and the other at 11:00, usually with three bands playing per show. Graham always had the best artists in the city.

His wonderful eye for talent and an ability to mix different styles of music at the same shows was always surprising. I recall seeing Miles Davis opening for Neil Young with Crazy Horse and Jethro Tull opening for the Jeff Beck Group with Rod Stewart… strange mixes but the Fillmore was always introducing audiences to artists that wouldn’t have gotten as much exposure otherwise. Happily, I had chance to meet and talk with Mr. Graham years later because Joe Satriani was working with Mick Jagger, but that’s another story.

The Longview was the spill-over bar across Park Ave from the notorious Max’s Kansas City, long before Max’s had live music. My friend Jack Abbott, a publicist, introduced me to both places. He said they were “hip” (it was the 60s) and he was right; there was nothing quite like either of them.

Jack knew Micky Ruskin and would go across the street to the super-crowded Max’s and find out about the gallery shows or loft parties that we could crash. I would wait at the Longview, happily engaged in conversations, engulfed in the ever-present mist of patchouli oil and cigarette smoke.

Needless to say, more than a few evenings ended with me suspended on the modern art swing in the entryway of the Long View soaking up the last few minutes of night life before closing time. I usually walked up to the 59th Street Bridge to save money before catching the bus back to Astoria, Queens. A lot of the store windows on the way uptown were even better than the art shows that we crashed.

Max’s and The Longview were both owned by Micky Ruskin and known for being artist hangouts for “the in crowd”. Each club had their own style. Max’s was star studded with Andy Warhol holding court in the back room and rockers and Hollywood types cruising the bar and tables. Micky was at the front door to decide who should be let in and this was long before Studio 54.

The Longview, on the other hand, (on the corner of Park Ave South and 18th Street) was more like a gallery, well-lit, friendlier, and much quieter.

We already had our own music, fashion, art, films, haircuts, and there was an almost irresistible energy. And a shit ton of in with the new and out with the old.

I was interested in people with talent, and you could find a good mix of everyone from poets and painters to musicians, secretaries, or lawyers… and a lot of uptown meets downtown. Being drug free, my concept for expanding my consciousness was to hang out with people that were smarter than me.

The Woodstock Festival was due to begin on August 15th, 1969, and was billed as a Music and Art Fair… “an Aquarian Exposition”. I knew my generation was going to change the world. We already had our own music, fashion, art, films, haircuts, and there was an almost irresistible energy. And a shit ton of in with the new and out with the old.

August 18th was my 20th birthday and New York was a city of dreams and anything was possible.

I never made it to Woodstock that summer and as fall became winter, I continued with my normal routine: college classes, shows at the Fillmore, hanging at Longview and band rehearsals.

I was with students protesting the Vietnam War at Staten Island Community College in May of 1970, when we got the news that the National Guard had opened fire at Kent State. It seemed that America had suddenly gone topsy turvy and all the things that seemed loving and possible the summer before had changed.

By the end of June, I was still in shock but took my regular summer job as a concrete laborer working at the City University at 138th Street and Convent Avenue (a job I got with the help of my cousin’s husband Tony.)

Working construction got me enough money to go to school and get by with a part time job during the school year. Although, I preferred my previous job at the Record Center located across the street from what was to become Electric Lady Studios on 8th Street, I made twice as much money carrying steel scaffolding and 4-foot by 8-foot sheets of plywood across the roof top of the new science building instead of selling records.

The events of May 4th at Kent State left me bewildered and disappointed. When the fall semester of college started, I dropped all my electronic engineering classes and became a full-time music major with a minor in film. That winter, I moved in with my girlfriend. She lived only two blocks from Richmond College in St. George. Now the hours previously spent traveling on the subway and ferry from Astoria to school (two hours each way) were put to better use: playing guitar.

I had been working on and off with several bands in Queens, but the work was never steady. My goal was to make a living playing music, but my current band “Gas, Food and Lodging” never worked enough. The backup plan was to get a job as a music teacher, like my friend Brooke Ostrander (soon to be Wicked Lester), who was the keyboard player in my band. He managed to play clubs with me and teach at a grammar school in New Jersey. I helped with a lot of his classes and encouraged the idea that grade school music programs should extend beyond the traditional music program of orchestra and John Philip Sousa. I wanted to teach popular music.

I had become friends with Gene Simmons the previous year (soon to form KISS) and he came to a bunch of our shows. Our classes ended at about the same time, so we rode the subway back to Queens together regularly. He was bright and funny, and we talked about music, guitars and women. He lent me his 100 watt Marshall bass amp for a few of our gigs and we made some recordings in my family’s basement. There was a plan to put a band together at one point, and he introduced me to Stan Eisen (soon to be Paul Stanley of KISS). We played together once but they wanted to do originals and I wanted a working top 40 band. Gene told me that he was going to be a rock star and there was always something special about him and I believed him… and he did.

I had also reconnected with my high school (Brooklyn Tech) friend Tom Morrongiello (later to become Bob Dylan’s guitar tech among others). Tommy had grown up on Staten Island and knew all the local clubs, bands, players, and introduced me to everyone.

Staten Island had a thriving music community and club scene was partially driven by the difference drinking ages between New York (18) and Jersey (21). The big bridge crowd kept the venues full, and you could play clubs on the Island for months without ever leaving.

Game Changers

At the time, I was playing a late 60s Gibson Barney Kessel (definitely not a rock guitar) and Tommy mentioned that he had a beat-up Stratocaster that I could borrow.

The Strat was truly beat-up, it had a broken middle pickup and the rosewood fingerboard was so badly worn there were ruts in it. The strings didn’t align properly with the neck and someone had spray painted the body white.

Being a Brooklyn Tech boy, I set out to fix it. After all, it was a Strat and Hendrix played a Strat.

I replaced the broken middle single coil pickup with a Gibson humbucker that I got somewhere on 48th street. I knew it would be quieter but when I finished the install, much to my disappointment, the strings didn’t line up with the humbucker screws and it was much louder than the Strat pickups.

After giving it some thought, I decided to completely rebuild the guitar.

First, I made it stereo so the mismatched tone and volume of the humbucker could be adjusted by using the second channel of my Fender amp. Added a Boss distortion unit under the pickguard and I connected it directly to the humbucker. (See diagram.) I wired the humbucker volume control after the circuit so the distortion was always set at max but the output could be controlled and mixed with any combination of pickups; or you could bypass the distortion out of the circuit.

My new wiring had a second three position (Gibson right angle switch), two volumes, and one tone control. This way you could have any pickup combination including all.

I put a mini toggle switch at the output jack so I could switch between mono or stereo.

After finishing it I realized that I’d never seen any guitar circuit design like my hot-rodded Strat. I solved the string alignment problem by rebuilding the bridge with modified Tele parts, stripped the finish and sprayed it with clear Krylon lacquer, and it all worked.

Later that week, I went for my regular guitar lesson in Brooklyn with Jack Wilkens. I brought my newly completed and highly modified Stratocaster that day. I either played well or Jack liked what I had done to the guitar but at the end of the lesson he asked, “What are you doing after this?” I responded that I had nothing to do. He invited me to come with him to Dan Armstrong’s guitar shop in Greenwich Village. He was thinking about buying a solid body guitar. The musical director of show “The Me That Nobody Knows” (a rock musical) thought Jack needed a more electric guitar sound for several of the songs and Jack’s Gibson L7 wasn’t cutting it.

Armstrong’s shop had the reputation for being one of the coolest places for guitars in New York City. Dan had already designed his “see through guitar” for Ampeg and there were several in the shop. There was a lot of clear plastic design going around lower Manhattan at the time… tables chairs, lamps, etc. I loved the look of the Ampeg but hated the sound and thought it was far too heavy and said so, not making any points with Dan. Jack ended up borrowing a 50s two pickup Les Paul TV and we were off to the Orpheum Theater in the East Village to setup for the show that night.

Arriving at the stage door, we headed to the pit and… it was a pit. The band was completely covered by the stage and the floor was actually dirt. You had to bend down to walk around and only the musical director’s head protruded above the stage so he could see the action and direct the band.

I restrung the borrowed Les Paul with Jack’s favorite strings (nickel with a wound G) and got it up and running by show time. The director took a liking to me and let me sit next to him in the covered head space above the stage. From there, he cued the musicians and play keyboard. It was the best seat in the house, and you could almost touch the actors. Jack switched between his L7 with a DeArmond and the Les Paul several times during the show.

After the show, all the musicians were going to Chinatown for dinner, and I was invited to go along. At the end of dinner Jack again asked, “What are you doing after this?” I again responded that I had no plans.

It was like a musicians’ “Fight Club”. A song would start, and the solos began, and they went everywhere at breakneck tempos.

We took the train uptown to a rehearsal studio in the 40s on the westside. It was being used that night for a musician’s only jam session being hosted (I think) by the Brecker Brothers and it was… take no prisoners. There were studio session guys, Broadway shows guys, TV band guys, Juilliard guys, and players that wanted to test their skills. It was like a musicians’ “Fight Club”. A song would start, and the solos began, and they went everywhere at breakneck tempos. I wasn’t in that class of player but it made me want to push myself so I might be.

Jack played the first song or two with his L7 and asked if he could try my Strat for the next round. My guitar was set up for rock with .09 to .42 strings and the action was as low as it could go without buzzing. I gave Jack a quick usable sound and showed him how to turn the distortion on and off.

Jack had fun with the guitar but it wasn’t his thing. The night ended at about three in the morning and I got on the train to go back to Staten Island. My mind was buzzing with ideas for sounds and a deepened commitment to be part of the professional New York City music community.

A week or two later Jack told me that Charlie LoBue was looking for someone to work at his guitar repair shop. I called and Charlie he told me to stop by the next day. When I arrived at The Guitar Lab, I was greeted by a number of scowling faces. I asked if Charlie was there and he told me that they were having a meeting and I’d have to come back tomorrow. When I returned the next day Charlie explained that he and Carl Thompson were breaking their partnership and Carl was moving out of the shop.

I demonstrated my rebuilt Stratocaster for Charlie and got hired on the spot. At the time, I didn’t realize that Charlie had no understanding of what I had done to my Strat but I happily accepted his offer of two street dogs (lunch) and $10.00 per day to work at his shop. I could easily fit two days a week plus Saturdays around my class schedule and start that week.

The Guitar Lab

The bulk of our work were setups, neck adjustments, restringing, re-fretting, with minimal electronic work. I thought that Charlie would promote what I had done to my Strat in the shop but that never happened. Most of my electronic work became removing mini humbuckers from Les Paul’s, routing the holes bigger and replacing them with full size humbuckers or pulling neck pickups out of Tele’s and doing the same.

The Guitar Lab was an authorized repair center for both Gibson and Fender, so Charlie could buy factory parts direct. For about six months the shop was just me (part time) and Charlie.

Charlie showed me how to re-fret guitars and within a month I could do a complete fret job in half a day plus a bunch of other tasks and run errands.

Neither Gibson nor Fender spent much time doing final setup of their instruments. It was common knowledge that pre-CBS and the pre-Chicago Instrument and Norlin era guitars were far better than their new guitars. As far as I was concerned, the corporations were doing just about everything wrong, from bad woods and heavy polyurethane finishes to changing magnet sizes in the pickups. The new guitars were a mess and mere shadows of their former excellence.

I felt that vintage Gibsons and Fenders were works of art. Not to say everything old Gibson or Fender is great, there were some real mistakes back then too, but the good ones were wonderful. The electric guitar is an American art form. From the screw on neck style of Leo Fender’s Telecaster and Stratocaster to the more hand-built quality and precision of Gibson’s Les Paul and 335 designs.

By the end of my first month with Charlie, I changed what he was offering to a more of a rock guitar package. For example, a brand new Les Paul would come into the shop for a setup, and I would suggest that we remove the pickup covers (getting the pickups closer to the strings), do a grind and polish (Gibson’s fret work was particularly bad at the time), recrown the frets, restring with Guitar Lab .09s, adjust the neck to accommodate the reduced tension, and re-intonate the bridge. Then reset the pickup heights and individual screws for better string balance… a real setup for about $35.00.

These were the final steps that Gibson should have been making but wasn’t. We kept getting more and more business because when I was finished, the guitar played and sounded better than what came from the factory. Charlie had a sign on the wall that said, “Everyone that wanted nines and the action as low as it could go, should leave the shop now”. But that’s exactly what I wanted, and I could deliver it. I was the right guy, with the right skills in the right place at the right time.

Being at the Guitar Lab was an education every day. When someone came to pick up their guitar, they played their best licks or favorite song. There was always a new trick or phrase to learn.

We received a lot of referrals from the 48th street stores. Back then, Manny’s was king of the block and most of the celebrities bought from Henry Goldrich at Manny's. He papered the walls of the store with framed autographed artist photos, and you never knew who you were going to run into trying out an instrument. Henry and the staff gave everyone a hard time; you couldn’t even try a guitar unless you showed them you had the cash to buy in your pocket. Of course, there were exceptions to the Henry’s rule. Jimi Hendrix loved Stratocasters and Henry always had the largest selection in the city. Hendrix would go to the store after hours so he could play a bunch and pick his favorites. The famous Black Beauty and Olympic White Woodstock Stratocaster were off the shelf Strats from Manny’s.

Henry liked me, and Manny’s had all the newest and best gear in stock so they were always my go-to shop on the street.

The Guitar Lab quickly got the reputation of being the best repair shop in the area, so we got a lot of the session players. We were on good terms with all the shops on the street, and they felt comfortable sending work to the Guitar Lab. We didn’t sell anything except our own strings and the occasional used amp or guitar.

Being at the Guitar Lab was an education every day. When someone came to pick up their guitar, they played their best licks or favorite song. There was always a new trick or phrase to learn. I would say, “Please show me that again”. Sometimes it was a bend, a slide, or a chord inversion. All the sheet music books at that time got the chords wrong for songs as well as the fingering. In that pre-YouTube world, if you wanted to learn a part of a song you either played the record over and over or watched a live show to figure out the hand positioning. Another wonderful thing was that I got to take apart the best old guitars. Teles, Strats, 335s, L5s, Les Pauls, basses… everything made its way to the Guitar Lab. All the guitars and basses that people were talking about in Guitar Player magazine — I got to see and play the real thing.

The Guitar Lab was around the corner from 48th street (“Music Row”), and that was a worldwide musician’s destination. If you wanted anything musical, you came to the street. Everyone stopped by the Guitar Lab, especially people that were playing at the Fillmore or local clubs. I don’t think Charlie ever ran an ad and everything was by word-of-mouth referrals from players. I eventually brought Gene Simmons and Paul Stanley to the Guitar Lab to meet Charlie.

Sometimes on my way back to Staten Island, I would get off the train at either Canal or Cortland streets and cruse the electronic supply, surplus, plastic, or hardware shops. I was always looking for parts, speakers, tools, etc. You never knew what you were going to find.

I wanted to replace a lot of the screws, switches, and pots that we bought from Gibson or Fender and use what I was finding locally. We were always running out anyway. One of my regular tasks was going to Eddie Bell Music and buy extra parts for repairs from them.

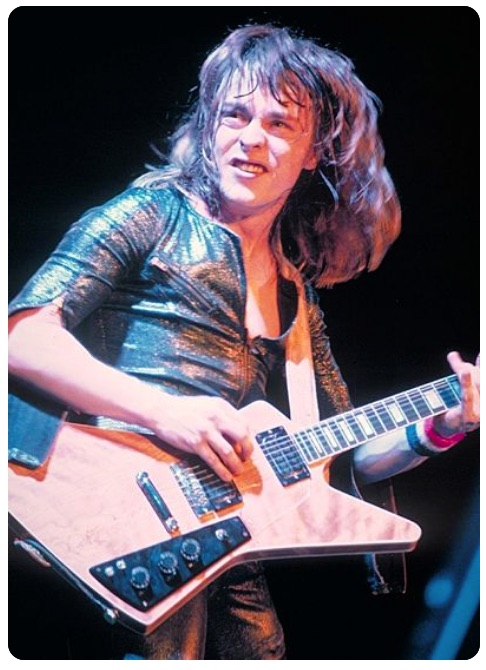

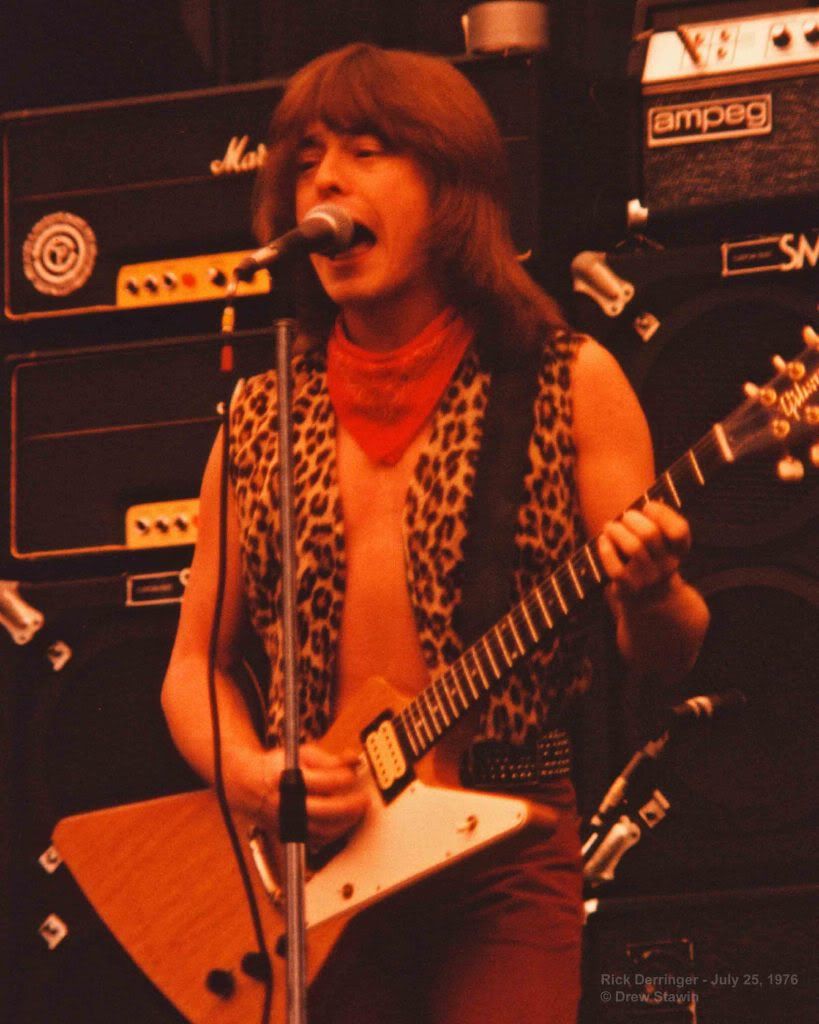

My favorite Cortland Street find at the time was a military grade mini-switch that I started using on my guitar rebuilds. (See Al Di Meola and Rick Derringer photos.) Eventually my mini-switches became standard on BC Rich guitars and basses, and I still included them with the DiMarzio Dual Sound® pickup. I eventually created an improved parts line for DiMarzio, and we still sell them today.

Charlie would send me downtown to deliver all the complicated guitar repairs (broken headstocks or neck resets) to Michael Gurian’s shop. Michael knew more about wood than anyone I’d ever met. He was building his own acoustic guitars at the time and always working on some new tool or production improvement. I wasn’t a fan of his guitars but Michael was salt of the earth.

From Repair to Innovation

One day, someone brought a D’Aquisto to the Guitar Lab to be re-strung before a show that night and I got to play one of the most beautiful arch top guitars I’d ever seen. The action was as low as it could go and still play and each note sounded as even as a piano. Everything was meticulous, especially the fret work and neck shape. I got Jimmy D’Aquisto’s phone number from Charlie and called him immediately. I told him how much I liked his guitar and the fret work. I explained that I was working at the Guitar Lab and he suggested that I stop by his shop. A week later I hitch hiked (I had no car) to Huntington, Long Island, and knocked at the door. Jimmy looked at the long-haired, rain soaked hippie standing in his doorway and I explained that I was the guy that called from the Guitar Lab.

I’m sure I was a surprise for him, but he generously showed me around the shop and we talked for a few hours.

I was expecting to see a small factory, like Gurian’s, but instead there were a few bending jigs, a drill press, a big buffing wheel, some hand tools, and Jimmy. It was all just him; it was his hands and his experience making these wonderful guitars.

He showed me the fret files he made and how he used them. He said he started with old beat up triangular and flat files, ground off the bottom cutting edge, and then polished the surface. “Don’t use new ones because they cut too quickly.” This lets you work the frets and not damage the fingerboard.

I eventually added 800 sandpaper to the mix and white car polishing compound buffed with a rag wheel after the red compound for my final steps… and you could see yourself in the frets.

Another one of his tricks was fret polishing. After the leveling and crowning the frets, Jimmy added more grades of sandpaper to remove the surface scratches left by the grinding stone. He started with 320 and progressed to 400 and finally 600. He finished with 000 steel wool before buffing the fret board with red car polishing compound. When he was done, you could practically see your face in the frets. They had a broken in feel when it left the work bench

I felt Jimmy’s fret method was perfect for rock and blues players since we were always bending notes.

He was making non-adjustable arch top bridge and solid ebony tail pieces for his guitars at the time. He felt that both delivered a better string balance and I thought they also increased the volume acoustically. Jimmy told me he was working with D’Addario to develop his own line of jazz and acoustic strings.

The next day I used the Guitar Labs grinder and buffing wheels to make Jimmy style fret files. I rapidly incorporated everything I’d learned from Jimmy with what Charlie had taught me and soon my fret work was almost as good as Jimmy’s. I eventually added 800 sandpaper to the mix and white car polishing compound buffed with a rag wheel after the red compound for my final steps… and you could see yourself in the frets.

I started getting a lot of fret work because of the improvements. I began experimenting and putting a quarter turn on the truss rod before leveling the fingerboard (after removing the frets). This way the truss rod was always active, even with .08 strings.

When Jimmy’s new strings were finished, I brought them to Charlie hoping that he would sell them at the Guitar Lab. Later, when I opened my shop, I used Jimmy’s strings exclusively for all my acoustic guitar work.

I was still making $10.00 a day and two hot dogs when Charlie started bringing in more workers. He told me he wanted to build guitars and asked me to show Woody Phifer how I was doing frets. Within a short time, his fret job was as good as mine.

In an effort to get more work, I asked Charlie if there was something I could take home. He handed me a box of broken pickups that had been collecting under his work bench for years and said, “Fix these”.

There were dozens of broken pickups of every kind, from all the major manufactures and I liked taking things apart anyway.

I had tried my hand at rewinding the coil of my broken Strat pickup but it was a failure. I used a record turntable, the only motor I had, but the magnet wire kept breaking and I would have to start over.

Eventually used an old Gilbert Erector Set motor, geared down so it would be slower with much the same result. I did finally get the Strat coil wound but it sounded terrible, so, I gave up for a while. My problem was how to get the wire off the spool and on to the bobbin without breaking.

I made notes on everything that I took apart and kept samples of the wire and magnets when I could… it was quite the education. Having studied electronics at Brooklyn Tech and my engineering work in college, it all started to make sense.

I started working through the box of broken pickups, checking for cold solder joints or shorted connections. Sometimes I could save a pickup by just pealing a few turns off the coil finish and resoldering. Others just needed to have the leads replaced. While working through the humbuckers, I realized that I could salvage the working coil and match them up — screws and stud — from another pickup from the same period and reassembling the pickup, and I got most of them to work. Charlie’s process was, if a pickup didn’t work, he replaced it with a new one. I felt that destroyed the collector’s value of a vintage instrument and it bothered me.

I managed to fix most of the box from the Guitar Lab and brought all the working pickups back and Charlie gave me $10.00 for my efforts.

I made notes on everything that I took apart and kept samples of the wire and magnets when I could… it was quite the education. Having studied electronics at Brooklyn Tech and my engineering work in college, it all started to make sense.

Then, I had an idea that might solve my winding problem. What if I turned the magnetic wire spool on its side and got it spinning at the same speed as the coil motor? That might work. So off I went to the toy store to get roller skate wheels (ball bearings) and the plastic shop on Canal Street for some rod stock that would fit through the wire spool. I suspended the spool between the roller skate wheels and the spool was free to spin. This worked better but then the momentum of the spinning spool started going faster than the motor and I wound up with 50 feet of magnet wire across the floor. However, I did manage to wind a few humbucker coils wound from the Guitar Lab scrap box.

As the work for me continued to dry up at the Guitar Lab, I applied for the work study program at Richmond College and got a job in the music department. As it turns out, the chairman had just gotten a synthesizer that connected with lots of cables. (I think it was an early Moog) I built him a switching network that worked with 5 three way Strat switches like an old-style telephone operator switchboard. It worked great and he wasn’t pulling wires in and out trying to get the sounds he wanted.

By then, I had developed a good eye for vintage guitars and amps and started buying and selling whenever I could to help supplement my income.

I built a work bench out of scrap wood that I collected from building sites in the neighborhood and… I was in business for myself.

I started going to all the music stores on Staten Island and around the city to see if they needed repair work done that I could take home and bring back the next day.

One of the shops I visited was Bill Lawrence’s in Greenwich Village. When I got there, I was surprised to see Billy all alone in a very empty store front. I explained that I had been working at the Guitar Lab and showed him a Telecaster that I had recently rebuilt. I re-shaped the neck to be thinner like a 1959 335 and flattened the fingerboard to a 9.5-inch radius, installed large Gibson frets, and made a full-size uncovered humbucker for the neck position. The humbucker was built from the scrap pickup parts left over from the Guitar Lab box and my newly wound spinning spool coils and a large Gretsch Filter’Tron magnet (also from the scrap box). It was wired like a Gibson so the switch connected the neck, both or the bridge pickup and a volume and tone controls that worked with all the switch positions.

The flatter radius and bigger frets made bending strings easier. Most of these improvements were eventually incorporated into the DiMarzio Strat and Tele replacement necks that I produced with Stuart Spector (Spector Bass) but that’s another story.

My guitar must have shocked Billy because he said that he would rather work with me than compete with me. I was stunned, I knew my guitar work and wiring were good, but I didn’t think my humbucker was all that special. I didn’t really know what I was doing at that point. I could repair pickups, but the humbucker was just an experiment. Billy was impressed, and I took it as a compliment.

He was also very curious about my fret work, and I explained my entire process to him. (He incorporated my fret leveling and polishing techniques into the L6 Gibson that he helped design and it was released in 1973.)

He told me he and Dan Armstrong parted under bad terms. Then Billy and I started talking pickups. I told him about the Gretsch magnet that I used on my Tele humbucker and how I liked the higher output better than what I was getting from the new Gibson pickups. Billy took two magnets out of a box and handed them to me and said, “Try and pull these apart”. They were the strongest magnets that I’d ever felt. Although Ceramics were common in guitar speakers and were used in my all-time favorite, the original green and black back Celestion G12M-25, I’d never seen any used in a guitar pickup.

Then Billy opened a case that had a thin hollow body Framus with two of his new pickups mounted. The tops were made of brushed flat stainless steel and the coils were glued directly to the plate — no sides, no base. He plugged the guitar into a transistor amp with a JBL speaker and proceeded to demo the pickups and his coil switching circuit. They sounded squeaky clean and really bright. I wasn’t a fan of solid-state guitar amps and hated JBL guitar speakers, so it was hard for me to see what he liked about the sound. However, Billy did a great dog and pony show and knew how to pitch his ideas. The magnet demo was great, and his series/parallel coil switching was an innovation. When I compared his guitar to my Tele and his pickups were louder which I liked but harsh.

I asked Billy if he’d be interested in selling my Tele on consignment in the store and he said he would. I left it there and hit a few more shops uptown for more repairs.

About a week later I stopped at Billy’s shop to pick up some work and he had sold my Tele and paid me. I was playing in Queens that night and Billy said he’d like to come. He made dinner for us at his apartment, and we went to the club. “Gas, Food and Lodging” was particularly bad that night and Billy said so. He was confirming what I already knew but had hoped that the band could pull it together. About a month later I quit the band.

I continued getting repairs and selling guitars through Billy’s shop for about two months doing all the simple repairs in his shop and bringing everything else back to my apartment. He played every repair that I brought back to his shop — whether it was a nut replacement or a full fret job — and was very complementary about my work.

Bill Lawrence never showed me how to build or wind a pickup. I already knew before I met him and, other than our initial conversations about magnets, it seemed that he wanted to keep everything a secret.

By then, I was getting repairs from the Mandolin Brothers and co-owner Hap Kuffner introduced me to George Mell. George was a local Staten Island bass player and regularly on the road with various bands. He made a side business out of hitting pawn shops and music stores in each city looking for well-priced or rare instruments. If he found a good flat top guitar, a banjo, or mandolin it went to Hap and Stan Jay (The Mandolin Brothers). If it was a bass or arch top guitar, he sold them at the musician’s union himself. If he found a solid body guitar, I got the call. I would fix them up and bring them to Billy’s shop or if they were amazing vintage, I sold them to my customers.

Contrary to internet speculation, Bill Lawrence never showed me how to build or wind a pickup. I already knew before I met him and, other than our initial conversations about magnets, it seemed that he wanted to keep everything a secret.

I installed several of Billy’s pickups at his shop and I understood what he was doing but never saw any machinery or tools other than a screwdriver that Billy used to tap on a pickups to test them. Billy never made a replacement pickup until years after DiMarzio was successful. (See Billy Lawrence Stainless pickup.)

On one of my visits to his shop, I walked in on Billy arguing with a tall, slender, long-haired guy. I found out later, this was Artie. He worked in the basement of the shop and built all of Billy’s pickups.

We spoke one afternoon while Billy was out getting coffee and Artie was upstairs watching the store. Coincidently, he lived on Staten Island and was a violin player, so I suggested that we play together some time and we exchanged phone numbers. I think we played together once or twice and it was pretty bad, so, I didn’t think anything further about it.

I began to get the feeling that things weren’t going well at Billy’s shop. I remember him praying in the middle of the store for business one afternoon. I thought he was just being funny. Someone did come that afternoon to buy pickups, so I guess it worked.

Billy told me that he was going to try and sell some of his pickup designs to Gibson and I thought that I might be part of the package.

I knew I could make changes that would get Gibson back on track. The two most obvious being: just build the Les Paul and the dot marker ES 335 like you did in 1959 — same wood, same neck angle, same neck shape, same ARB-1 bridge, same pickups. I had worked on a number of these guitars, and they were magical.

Gibson needed to clean up their act and re-establish the company’s credibility with the players. It could have been done in less than a year and then I could start introducing my new guitar designs. At the time, I had ideas for a double cutaway, similar to the 335 for better access, improved neck shapes, and updated body contours since Gibson’s were so boxy and introduce new wood combinations, etc.

Escape From New York

A week or two later, I got a panicked call from Artie. Billy was leaving the next day for Gibson (Kalamazoo, Michigan) and he had to finish the demo guitar. I didn’t know until that moment that Artie didn’t know how to wire a guitar.

I said no big deal, come to my apartment and I’ll get it done. Artie arrived with an old Gibson Melody Maker, Billy’s winding machine in a backpack and his girlfriend.

I thought all I’d have to do was a quick wiring job, but the pickups weren’t made, and the Melody Maker required routing the pickup cavities larger as well.

I got the coffee pot on and Artie setup Billy’s winding machine up on the kitchen table. It was a surprisingly simple system with a wood base, a counter, a sewing machine motor, and an on-off switch. You fed the magnet wire on to the bobbin by hand… super simple. Then my jaw dropped when Artie just put the spool of magnet wire on the floor (vertically) and the wire pulled straight up the top of the spool. Not like any of the stuff that I was doing. I laughed and showed Artie the spinning spool winding setup that I had made.

Artie, unintentionally solved my biggest winding problem, getting the wire off the spool in one piece. He got to work winding the pickups and I started on the guitar.

There were no instructions from Billy on what to do, other than he was taking it to Gibson. To help make a better presentation, I made a brand-new pickguard from ¼-inch cream colored plexiglass and did a complete grind and polish on the frets.

I modified a set of pickup mounting rings so Billy’s stainless pickups were parallel and closer to the strings. I then wired both of Billy’s pickups with my mini-toggle switches for series or parallel connection. This way you got eight sounds from just two pickups, something that Billy invented. (He really liked doing the wiring that way.) I thought that only a few of the options sounded okay but that’s what Billy liked and that’s what I did.

I got the guitar finished late that night and Artie was relieved. He thanked me, packed up Billy’s winding machine, and headed to Queens to deliver the guitar. I was happy with the guitar, it looked good and played great.

A week later Artie called and told me that Billy was gone. If I wanted the guitars that I had left at the shop, I had to meet him that morning. My response was WTF!

When I arrived, Artie was already in the shop, and he told me that Billy had taken a job at Gibson and wasn’t coming back. I found out that Billy hadn’t paid the rent on the shop for months and the landlord was changing the locks that day. I don’t think Artie was getting paid either. Since I didn’t work for Billy, I always got paid for my repairs when I dropped them off.

I packed up my guitars and we looked around the shop. There were a few of Billy’s magnets, bobbins and stainless-steel covers left in a box but the store was completely empty. I asked Artie if he wanted the pickup parts and he said, “No”, so I took them. I had the feeling that he was over working on guitar pickups and with Billy.

Neither Artie or I got paid for finishing the Melody Maker and I never heard a word from Billy. He was gone along with my dream of designing guitars for Gibson.

Years later after Billy left Gibson we met again when he was working at Gracin’s Music on 48 street. I was dropping off DiMarzio pickups to the store and he never said a word about the way he left New York. I was president of DiMarzio by then, so it didn’t make much of a difference.

We stayed on friendly terms, and he would always stop by the DiMarzio booth at trade shows around the world. I think he was secretly proud of me and the success that DiMarzio was having.

The Mother of Invention

After seeing Billy’s winding machine in action, I decided to build a new winder for myself, and make some improvements. I went to Canal/Cortland Street and got a sewing machine motor and a counter, hit the local construction sites for scrap wood, and built my new winder without any power tools.

Feeding the wire on by hand (Billy style) wasn’t accurate enough for me and I wanted better control of the magnet wire and how it layered on the bobbin. I came up with an idea for a right-angle feed to the bobbin. My design was like a machinist’s lathe, using a slider that was parallel to the axis of the counter and could be moved back and forth (good old Brooklyn Tech machine shop classes). I added an adjustable tension clamp, made from Erector Set pullies, to the end of the slider with foam between the two plates to control the wire tension.

… what was previously taking me hours could be done in a tenth the time.

I was still getting some wire breakage until I added a 2-inch piece of glass tubing as a wire guide. This let me focus where the wire landed on the spinning coil. I melted one end of the tube on the kitchen stove to reduce the size of the tube and it improve the wire focus when it landed on the spinning coil. The other side was left open for easier threading. By the end of the week a had built my own fully functioning winding machine. Now, what was previously taking me hours could be done in a tenth the time.

Always looking for more work, I stopped at We Buy Guitars on 48th street. I asked Mr. Friedman of We Buy if he had any guitars that needed repair. He told me they had a full-time repair man on staff. Then I thought, “I’ve got a winding machine,” and I asked him, “Do you have any broken pickups that need repair?” He showed me a large box full of broken pickups. We agreed on $6.00 each and I took home all the pickups that I could carry. He was very happy when I returned them a week later, with all of them working, and he gave me more pickups to repair.

With the steady flow of broken pickups, I began experimenting as well as repairing. Strat pickups were a good place to start. It was a popular guitar, and I was very familiar with the shortcomings and the construction problems that were inherent Fender’s design.

I methodically began listening to the sound changes that would happen when I altered the turn counts or made wire gauge changes for my repairs. I had also worked on dozens of mid-to-late-50s Strats and they all had the same bridge pickup issues. While I loved the sound of the Strat neck pickup, I felt that the bridge pickup left a lot to be desired. So, I set out to change the character of the bridge pickup. I wanted a warmer, louder, fuller sound that would blend well with a distorted amp.

Refining the Sound

By now, I was playing a late 50s Fender Tweed Deluxe amp that I had heavily modified. I changed the power supply from a tube to solid state, installed a 16 ohm Celestion speaker, and swapped the 6V6s for 6L6s tubes (without re-biasing). My modifications made for a wonderful distortion when you turned the amp up (without using one of those terrible fuzz boxes of the time). Everything was mismatched on the amp, and it sounded great. Another advantage was that it was loud enough (15 or 20 Watts) to get past the drummer, but you didn’t overwhelm the room when you turned the guitar volume up for a solo and get it into distortion (and the bartender didn’t hate you). If I needed a bigger sound, I added a Marshall 4X12 bottom that I rewired down to 4 ohms.

Years earlier, I had gone the route of building a Dual Showman style amp from the Fender schematic. I used the RCA manual to make some circuit improvements and over-speced all the parts, especially the output transformer and power supply. I was working in the warehouse at Lafayette Electronics at the time and they had a great parts catalog. It was a super clean hifi like guitar amp. Everything was overbuilt, and it was ultra linear. It made a great PA amp but sounded terrible with my guitar. I had learned my lesson: linear doesn’t mean better when it comes to the guitar.

Tommy Morrongiello was also doing amp mods and he showed me how to rewired the bright switches on a Fender Super Reverb or Twin Reverb amps to bypass the tone circuit and the other channel bright switch to bypass the feedback loop (similar to a full on Presence control but dirtier) on the output transformer. Both switches could be used to add distortion or clean up the amp.

I began by winding my Strat repairs with the tightest coils I could make and filling the bobbin, so the plastic cover barely fit over the coil. Everything was tested in with the Deluxe and I kept records of the resulting sound changes and the modifications that I made on each pickup. Some of pickups got too fat and wouldn’t fit through the pickguard so the experiments continued for months. My work became finding a way of rebuilding an existing Strat pickup to be more modern sounding, yet you could return the guitar to stock if you wanted. I concluded that it had to directly replace the stock Strat pickup. This also meant, combining with the other pickups in the guitar as well. And there had to be a quality to the distortion.

Before my pickup approach, there were rumors of how to get a good, distorted sound. Everything from cutting the speaker with a razor blade to turning the volume all the way up and adding reverb but none of these options worked easily in a club environment or blended smoothly into the show.

When I first heard Keith Richards’ 1965 (Maestro fuzz) guitar sound for ‘Satisfaction’ I liked it but it couldn’t compare to Clapton’s 1967 sound on ‘Sunshine of Your Love’. Both were distorted, but one is a transistor distortion and the other was an organic tube distortion. I loved Clapton, Page, and Jeff Beck’s more natural distorted guitar sounds but the problem was how to get that sound in a club. The tubes had natural sonic authority that the fuzz tone circuit lacked. I had a lot of experience with the Boss fuzz that I had built into my Strat and I tested every new pedal that Manny’s had but none of them really got to the sound that I wanted.

I started giving samples of my favorite Strat bridge pickups to a local guitarist/singer Jimmie Mack to try out. Jimmie was the Bruce Springsteen of Staten Island and was always working with his brother Jackie and sometimes Earl Slick (soon to be David Bowie’s guitarist). He loved his Marshalls and I only had Fender amps, so I had the added advantage of being able to hear my pickups live in a Marshall.

I introduced Jimmy to the owner of the Hayloft (a local club) and Mack Truck became the house band. I got to listen to how his guitar sounded in the room and how it fit in with the band. I must have rewired his guitar two dozen times. Sometimes as a treat, I got to sit in with them for the last song or two of the night. My corrections to the bridge pickup became a game changer.

Within a few months, I had a winner and I had invented the world’s first replacement guitar pickup. I didn’t know it at the time, it was just another upgrade that I offered from my repair shop to my customers.

This Stratocaster modification eventually became part of the DiMarzio pickup line, and originally named the Fat Strat and now it’s the DiMarzio FS-1™. (I had to change the name because Fender trademarked Strat.) Yngwie Malmsteen used the FS-1™ early on and said in his memoir, “I put that sucker into my Fender and was blown away. The sound was awesome”. The Edge (U2) still uses FS-1s in his signature Fender guitar. David Gilmour used the Fat Strat (FS-1) in his “Black Strat” and it was used live and on some of the tracks for Animals and The Wall.

The Super Distortion

In the spring of 1971, I was working at Richmond College helping to setup the sound system for a dance company performance when the chairman of the department asked me if I wanted to play the school graduation party. I didn’t have a band at that time but knew that Gene, Brooke, and Paul had put together their new band. Gene had called me a few months earlier, asking if I wanted to play guitar with them. I still wanted a commercial band, so I opted out. But my first call for the college job was to Gene. I asked if he wanted to play the Richmond College graduation party and he said yes.

He stayed at my house that night since it was late when he finished the job. The band was “Rainbow”, soon to be renamed “Wicked Lester”.

There’s a bit of an internet mystery as to why Gene and Paul played at Richmond College… that’s how it worked, Gene was my friend and I got him the job.

Before the show Gene stopped by the house to get ready and I showed him my new hot Strat pickup.

Soon after, I started working with a local Chicago style band “Odyssey”. We were getting enough work that I could finally afford a Les Paul. I found out that Tommy was selling one cheap. He had converted an early 70s gold top Deluxe from mini humbuckers to full size humbuckers and thought the pickup might sound better mounted directly to the body, like a P90. He drilled the pickup mounting screws from the back of the guitar to mount the pickups. Within a short period of time, I was rebuilding the Les Paul and now was the perfect time to dig into my humbucker design.

I used what I had learned from my Strat pickup success, I was going to build a humbucker, eq’ed to have the tone I wanted and a higher output to keep the amp sustaining/distorting naturally and longer.

Central to my vision for my new humbucker design was it had to be a direct replacement for the existing Gibson pickup like my Strat pickup. This was very different approach to what I was doing at the Guitar Lab or what Bill Lawrence offered from his shop. Billy’s Stainless pickup wasn’t a direct replacement for a full size Gibson humbucker and no matter what you brought to Billy, a Strat, Tele, Les Paul or 335 you got the same pickup, the stainless humbucker. There were no size replacement for Strats, Teles or bass designs.

For me everything had to be size replaceable so you could always return the guitar to stock if you wanted.

I felt that there were mistakes in Billy’s stainless pickup design starting with the cover plate. It was ugly and not easily adjustable. Billy’s pickup was crude and never looked like it belonged on the guitar.

He chose to let the ceramic magnets do all the work. The design was further compromised because he reduced the polepiece head dimension further reducing the sustain when you bent the string. He widened the space between the coils to accommodate placing a magnet between the two coils for the Jazz version of the pickup. This way he could use the same parts for a thin mount Jazz style guitar pickup as well as his solid body pickup. (He used the middle magnetic placement later on his acoustic sound hole pickup.) Neither application worked well, and the wider coil space also changed the low end of the pickup for guitar.

Maybe it was because of my Brooklyn Tech education or crashing all those gallery shows, I had already routed a ton of guitars at the Guitar Lab and changed the pickups and it didn’t make sense to me. There had to be a better solution for getting a better sound and being able to get the advantages of both types of guitar in one guitar. When you put a Gibson pickup on a Fender style guitar the strings don’t line up with the pole pieces… Eddie Van Halen was aware of this and that’s why the bridge position humbucker is twisted on Frankenstein. He wanted the humbucker power from the bridge position of a Strat style guitar with a tremolo bar.

I needed an ingratiated solution for solving the problem and not destroy the vintage value of the guitar. If anything, I wanted to improve the look and you could always return the guitar to stock without having a gaping hole in the guitar or replacing the pickguard.

It’s similar to how I see the evolution of the contoured Stratocaster body shape design developing from the success of the slab Telecaster. Internet stories vary from Bill Carson telling Leo Fender that the new Stratocaster should, “fit like a shirt,” to simply getting rid of the edges of the body shape that didn’t fit comfortably against your body.

My feeling was that the Stratocaster body shape has a distinct California style. Southern California being a beach community plays a part in the more modern design. The modern curves, colors, and contours of the Stratocaster vs the Telecaster have always said surfer to me. It’s like the difference between a one-piece bathing suit and a bikini… related but different.

I knew that my pickup designs had to integrate the same way. They should of course improve the sound of the guitar — being much better than the original pickups — and add to the distinct appearance of the guitar.

I was still getting a few days a month at the Guitar Lab, so I talked Charlie into ordering some Gibson pickup bobbins and base plates from the factory for my project. This was out of the ordinary for the Guitar Lab and they never ordered pickup parts prior to my asking for them. Charlie placed an order for six bases and twelve bobbins because he didn’t want to draw any attention to the fact that I was building pickups from scratch with Gibson parts. To my surprise, they shipped the parts, they arrived a week or two later, and I got to work.

I’d recently seen Mountain and thought that Leslie West had one of the best live guitar sounds that I’d ever heard. (The recordings never did him justice.) There was a reason that the band was named Mountain: Leslie’s guitar sound was gigantic. He was playing a Les Paul Junior at the time but it wasn’t the sound of any Junior that I ever played.

I worked with Leslie years later but that’s another story.

I was learning more about controlling my tone and how the output of my humbuckers was affecting the distortion I was getting.

I began my humbucker design based on the success of my Strat pickup and Deluxe amp modifications. I still had a few of Billy’s ceramic magnets laying around, so I started with those. I overwound a pair of coils and when I assembled the pickup with one of Billy’s magnets, it didn’t fit the space under the coils properly, so I filled the gap with nails — the only ferrous material I had around the house — and held it together with tape and epoxy. I liked the new pickup much better than the stock Gibson pickups but it was still missing my imaginary benchmark: that huge Leslie West sound. Back to the drawing board… more pickups more tests.

I kept changing pickups in my Les Paul weekly and using them on the live Odyssey shows. The pickups were getting better, and my solos started to have the singing sustain that I wanted. Another part of the test was cutting through Odyssey’s horn section, which wasn’t an easy task. The band had gotten a large PA system and the horn players insisted on being mixed into the PA. Yikes!

I was learning more about controlling my tone and how the output of my humbuckers was affecting the distortion I was getting. I used up all the Gibson parts that I’d gotten from Charlie and only had a few stud bobbins left from the pickup scrap box and thought, “Why not go to see if any of the other repair shops have any parts”. As it turned out, no one had any pickup parts. Then I thought, Billy had been making his pickups with small Allen screws, why not try a large Allen screw that would fit the stud coil exactly and I could buy them at any hardware store.

I built the next pickup with 12 large hex Allen screws, a smaller gauge of wire, a tight layered coil, another ceramic magnet, more nails, and the result was wonderful.

I ordered some more pickup parts from the Guitar Lab and asked to have a guitar built to my specification. I loved my 335 and I wanted to experiment with double cutaway solid body design that I had been thinking about for years.

I traced a late 50s double cutaway Les Paul Jr that I had just worked on and gave the crew at the Guitar Lab my drawings. When the guitar was completed, the neck was off center to the body and they used a maple neck with an ebony fingerboard without asking me, and it weighted a ton. I hated the guitar!

My next order of Gibson pickup parts hadn’t arrived, so I built a pickup for the guitar from the leftover Billy bobbins. I made the cover from a block of scrap mahogany with my newly purchased Dremel motor tool. I added a three-point mounting so the pickup could be set parallel to the strings. (See photo.)

Billy’s pickups were never parallel to the strings and I felt my three-point mounting solved that part of the problem. I mounted the magnets the same as Billy but recalculated the coils.

I designed a shallow mount humbucker neck position and planned on using Plastiform magnets, like an old DeArmond design that I liked. The advantage would have been less magnetic pull at the neck position and I could avoid having to cut deeply into the neck to body joint. The deep cut created stability and tuning issues on the SGs, so staying out of the neck joint seemed a better solution.

I never finished the neck pickup, but everyone that tried the guitar liked the sound since it had a ton of output.

I decided to take the guitar to 48th Street and show it around and I stopped at Carl Thompson’s shop. That day, Steve Blucher was behind the counter and as it turned out, I recognized him as one of the scowly faced people at my first visit to the Guitar Lab. He told me he liked the sound of the guitar and asked if I would build him a pickup. I told him I had a better sounding pickup and built him a Super Distortion® when my Gibson parts arrived later that month, and we soon became friends. We saw eye to eye on a lot of guitar improvement ideas and he started sending pickup builds to me in Staten Island.

My Super Distortion® design was finished, and I was getting steady requests for the pickup.

I tried running ads (1/30th of a page) in the Village Voice and the Staten Island Advance without any success and all my clients were still referrals. Then I placed my first ads in Guitar Player magazine and people started contacting me.

Tommy Morrongiello was sending me fret and pickup work and I was referring amp mods and repairs to him. I mentioned that I was losing interest in Odyssey and he told me that he had gotten a call from a singer Bob Baskerville looking for a full time guitar player. I auditioned and got the job. Bob was paying $50 a night and working five or six nights a week all over New York and New Jersey.

The shows were usually six or seven sets a night of top 40 and sometimes we backed up oldies acts or stripers. I didn’t care much for the C, Am, Dm, G7th oldies bands, but backing up the stripper really improved my Wah-Wah pedal technique immensely. The club owners loved Bob and the work was steady.

With the extra cash I started buying and selling more vintage guitars.

I didn’t just want a vintage guitar; I wanted the best vintage guitars. My quest was to find best sounding late ’50s Les Pauls and 335s, and mid ’50s Teles and Strats to use as references for guitar and pickup designs. During the day, my apartment became a hangout for local guitar players and the coffee pot was always on.

While I was still getting repair working from the Mandolin Brothers, I made contact with other vintage guitar people and Dave De Forrest (The Guitar Trader) and I became friends. Dave was always hunting for vintage guitars and gear and knew exactly what I was looking to buy: the best. Dave was a buying and selling machine and created the first vintage guitar newsletter. He would also call me for electric guitar authentication (dates, originality, etc.) and repairs for his shop.

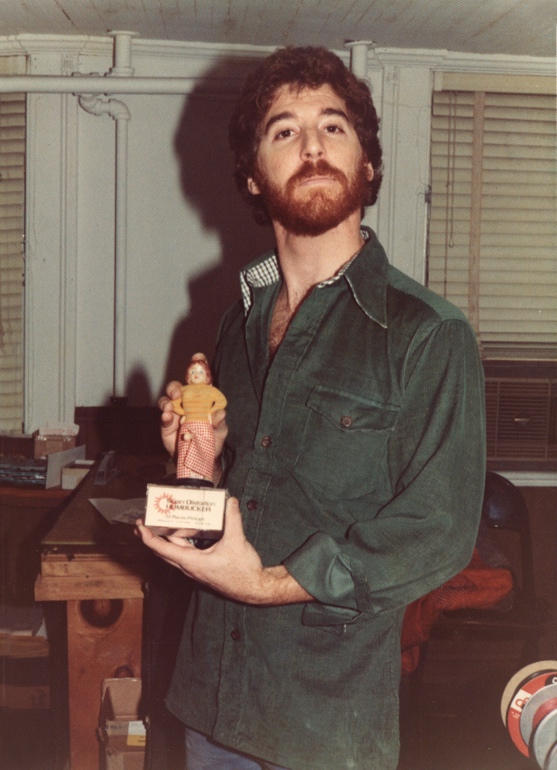

The photo below is me, Greg, and Bob. I’m playing one of the really good 57 Strats. I went through about six maple neck Strats, two Teles, and three 335s that year. (A real cherry sunburst Les Paul was still out of my reach because they were so expensive: $1,500 to $2,000) I played dozens of guitars before buying one and then each new guitar had to compete with the previous champion. The winner stayed on and the loser got sold.

My understanding of what worked live and why it worked was growing. I kept bringing all the new acquisitions to rehearsals and playing them at the clubs. My Les Paul kept getting a makeover at least once or twice a month, everything from neck reshaping to changing the color of the back to tobacco brown. Although the Super Distortion® always stayed in the bridge position, the neck pickup was always getting improvements.

The band was approaching a full year of steady club work. I was still doing guitar repairs at home and Alex of Alex Music on 48th Street asked me to help with his electric repairs, so I added a day or two a week there as well.

The other players in Bob’s band were all good players, and he was the best singer that I had ever worked with. I was bringing a rock edge guitar tone to the band’s traditional R&B and Pop style, and it was working. We were booked for two to three weeks in a row at most of the clubs and we were always working. My favorite venue was the dance club Barney Googles on 86th Street in Manhattan.

Out of the blue, Bob decided to bring back his ex-girlfriend as a second singer in the band (the ex-part didn’t last long). I was a hired gun and had no say, but once Hyla Parker arrived, my problems began.

Bob booked us on a three-month tour that start in Panama City Florida. He and Hyla wanted to break in the duo act on the road and planned it so we would work our way back up the east coast to New York playing clubs all the way.

This is exactly what I wanted: full time and on the road.

Hyla wanted the band to get custom-made matching suits, so before we left New York for Florida, we had them made. Now I was a hippie in a dark tan or blue satin suit.

I arranged for Steve Blucher to take my days at Alex Music with the understanding that I’d be back in a few months.

I flew to Florida with two of my favorite guitars: my customized Les Paul with the Super Distortion® in the bridge position and a prototype of my PAF® in the neck position. The second guitar was my prized original Gibson 1959 335 dot marker. (I still own that guitar.) When I got to the airport, they wouldn’t let me bring the guitars on the plane as carry on, so I bought them seats. I’d heard horror stories of guitars being damaged in baggage and I didn’t want to take any chances.

The flight was uneventful until we tried to land in Panama City. The airport was completely fogged in, and the pilot had to make six attempts at landing. Somewhere around the third try, I deposited lunch into the barf bag while the pilot continued circling and pulling up at the last minute. I got into a taxi and headed to the motel and there was this terrible smell. I assumed it was me, so, I kept my head half out the window. I found out later that there was a paper mill in town, and they discharged gasses several times a day. Luckily the motel was on the beach across the street from the club and the air was much better.

The band had driven down with the gear and within the first week of my arriving, Hyla stated complaining that I wasn’t funky enough for the band. In hindsight, I guess she wanted Cornell Dupree (who I love) but what she had was me.

One of our stronger songs was Stevie Wonder’s “Superstition”, our keyboard player even had a Clavinet. I usually Jeff Becked it with a twist of Leslie West and she hated it. I was moving in the direction of rock, and she wanted a strict R&B feel. The problems continued so I quit the band and waited for my replacement to arrive in Florida before flying back to New York.

I had only worked for three weeks in Florida, so when I got back to the NYC, I was completely broke. Between the flight costs, the satin suits, all the unforeseen expenses, and now no band and no job.

I asked Steve Blucher for some of the Alex days back and we began splitting the work schedule there. I sold off my 57 Strat, 53 Tele, 4X12 Marshall bottom, the Guitar Lab guitar, and a few vintage Fender amps for quick cash. I decided to make a go of my repair shop and moved it to the basement of a private house owned by my friend Pat Decicco at 88 Brewster Street in Staten Island.

Lift Off

Steve Blucher also started working for Charlie LoBue again at the new Lobue Guitars shop on Thompson Street and he recommended that Charlie use my Super Distortions in their guitars.

Charlie would order enough pickup parts from Gibson to accommodate his guitars production and some extra parts for me. I built all the Super Distortions at my shop in Staten Island, and I found a source for ceramic the magnets in Queens. I added cream-colored tape around the outside on the black bobbins to distinguish my work from stock Gibson pickups.

Sometime in 1973, I got a call from Ace Frehley. He told me that he was the new guitar player for KISS (I loved the name). Gene had told him about my guitar sound and the pickups I was making. Ace wanted to buy three Super Distortions, so we arranged to meet at the Staten Island ferry terminal.

It must have looked like a drug deal. Ace handed me cash and I gave him a brown paper bag. Then he turned around and got back on the ferry for the return trip to Manhattan.

It must have looked like a drug deal. Ace handed me cash and I gave him a brown paper bag. Then he turned around and got back on the ferry for the return trip to Manhattan.

I was invited to jam at a block party on Staten Island where Jimmie Mack, Jackie Mack, Earl Slick, and Hank DiVito (Nicolette Larson’s husband) were playing. One heck of a line up for a block party and I brought my Les Paul and sat in for a few songs.

I got a call from Slick that next week and he wanted me to put a Super Distortion® in his SG. He was going to an important audition that was setup by Michael Kamen (at the time New York Rock and Roll Ensemble). Slick wasn’t told who he was auditioning for, just that it was someone “big”. I rebuilt his bridge pickup into a Super Distortion®, did a grind and polish, and got the guitar back to him the next day. Turns out it was for David Bowie’s new band and Slick got the job. So, everything from David Live (Diamond Dogs tour) forward with Slick was a Super Distortion®.

Backstage and Loving It

Soon after, Al Di Meola contacted me and said that he had heard a lot of good things about my pickups. He came to the shop on Staten Island, and I showed him my Les Paul and he wanted to buy the guitar on the spot. I arranged to get him another early 70s Les Paul Deluxe and rebuilt it to be like mine except for the finish and neck reshaping — Super Distortion® in the bridge and Dual Sound® in the neck, fretwork: everything. Al asked me to rush the finishing the guitar so he could try it out for his next show.

I got to the “Return to Forever” show before sound check to deliver the guitar and Al liked the guitar so much that he played for the entire night.

Gene Simmons called me to ask if I wanted to go out on the road as a guitar tech for KISS. My guitar shop was starting to do well, so I said that I couldn’t but recommended Tommy as my replacement. He got the job and added roadie to this list of achievements. (It was Tommy’s first job as a tech.)

I got a call from Roy Buchannan around this time, and he mentioned hearing about my pickup designs and asking me if I would make a neck pickup for an old Esquire that he had just gotten. I went to see him at a club that night and his playing and tone were game changing. He gave me an early ‘50s Esquire and I decided to create a brand new Strat/Tele sized pickup design based on his sound and I included adjustable pole pieces. I got the guitar back to him a few days later and he loved it. This became the prototype for my next Strat design the SDS-1. Jerry Garcia used this pickup in the famous Doug Irwin-made Wolf guitar in conjunction with two Super Distortions.

The demand for Super Distortions was increasing and buying parts from Charlie was become unreliable so I decided to make my own.

I located a machine shop on Staten Island (Agostino Tool and Dye) that could make what I wanted but quickly realized I couldn’t afford an injection mold. Joe Agostino, the owner, suggested stamping the parts for the bobbins. I would have to assemble them with Acetone but I’d have a working bobbin for a fraction of the cost of an injection mold. (See photo.)

It’s a DiMarzio from 50ft Away

Then I had an idea, “Can we make the bobbins cream?” That way everyone would be able to identify my pickups at fifty feet away in a dark smokey club (just like my tape idea but better). I found a cream-colored plastic sheet that I liked, and I began producing the first DiMarzio Cream Super Distortion® pickups. Once I could afford a mold, I mixed my custom cream color that DiMarzio eventually trademarked and still uses today. I was making everything cream, even the company price lists and catalogues were printed on cream paper stock.

I wanted DiMarzio pickups recognizable from the back of the room in a dark club. Keep in mind that all of Gibson humbucking pickups including the “Patent Applied For” were made with metal covers soldered to the base plate. The Super Distortion® was the first no cover double cream bobbin humbucking pickup. I continued with my color identity when I designed my DiMarzio Model P®, DiMarzio Model J™ (the world’s first Jazz and Precision replacements), the SDS-1™, and more all in DiMarzio cream.

I made a few pickups for Alex Music’s guitars during this period (not Super Distortions) but Alex didn’t want to pay the price. Alex and I had a falling out over this, and he didn’t want to sell my DiMarzio pickups on 48th street.

Since I was already well known on 48th street, I simply walked across to Terminal Music. I asked the owner Artie Nitka if he wanted to sell my new pickups. He said yes, but I’d have to package the pickups. I thought, you’re only going to throw the packing away, but he gave me an order for six Super Distortions, and I thought, “Okay, now I have to design a package”.

The Packaging and Logo

I began to think that if Artie wanted packaging, I might as well make mine distinctive. Gibson didn’t sell pickups; they’re a guitar company. If you wanted a pickup it was for a repair, you ordered it through their parts department and there was no packaging.

On the way back to Staten Island, I had the idea to use a clear plastic box. This way you could see the double cream bobbins through the packaging. I took the subway down to Canal Street and found an AMAC box that was almost a perfect fit in one of the plastic shops. Next door was a foam rubber shop, and I bought some foam to keep the pickup from moving around in the box.

When I looked at the pickup in the box, it looked great, but it needed some sort of label. A week earlier I had seen Pat, my landlord, working on a circular mirror that he had added a medieval style gilded sun to in the center. I thought the sun looked like me. I had long red hair and a beard at the time. I went back to 88 Brewster Street and asked him if he could make some packaging cards that would fit my plastic boxes with a red medieval sun like he had done on the mirror with Super Distortion® Humbucker and DiMarzio written across it. The first six pickups were delivered to Terminal Music the next day with hand drawn cards made by Pat in my new clear plastic boxes, the same ones we still use today. Within a week Artie called me with an order for twelve more Super Distortions.

After seeing Rick Derringer on the cover of Guitar Player magazine, I asked Steve Blucher for Rick’s phone number. I called him and explained that I was the guy that made the pickups in his LoBue guitar. He was great and told me how much he liked the sound of my pickups and wanted me to install more of them in all his other guitars. He invited me to his apartment on 13th street and he gave me his original Cherry Sunburst to install Super Distortions.

When I asked him where he wanted me to put his original pickups, he told me to keep them. I told Rick no, he needed to keep them with the guitar; he might want them someday. I put his original Patent Applied For pickups in the compartment in his guitar case and he never put them back in the guitar. Then he gave me his original Explorer for a makeover as well. (See photos.) Rick was wonderful to me and he introduced me to New York’s best. We still work together and DiMarzio pickups are still in his signature guitars.

Steve Blucher introduced me to Steve Kaufman. He and his partner Harry Kolby were selling guitar and bass equalizers that mounted on your belt. (They didn’t have a foot switch and weren’t designed to be on the floor.) S. Hawk Ltd. was being distributed by the Kaman Corporation at the time, and they weren’t selling. The company reps were having problems selling the boxes so Steve planned on doing training sessions across America.

Blucher had shown Steve my pickups and they made their eqs sound much better. I tried his boxes but didn’t care for them and thought there were better ways of getting the similar benefits.

I re-built Steve’s Les Paul to use for his store demos with a Super Distortion® in the bridge and Dual Sound® (a Super Distortion® wired for series/parallel with my mini switch) in the neck. A month or two later, Steve was back in New York and told me that all the stores he visited wanted to buy my pickups but not his boxes.

Shortly after, he bankrupted S Hawk Ltd. and I hired Steve as DiMarzio’s first salesman. He had a photographic memory for people’s names and was familiar with every important music store in America. With his help, DiMarzio sales increased every month, and I had the money to make the tooling for the next round of my pickup designs.

I had already completed designs for my improved Tele, Strat, and EBO bass models. I changed both the construction and sound from what Fender and Gibson were delivering.

I’d done enough pickup repairs to know that a lot of the breakage on Fender pickups was due the vulcanized fiber that they used on the top and bottom of the coil form. It warped and often damaged the coil in the process. I made my Fat Strat (later named the FS-1™) and Pre BS Tele (later called the Pre B-1™) models using Lamitex which was about three times stronger, more stable material, and wouldn’t warp. I didn’t want any pickups returned because of bad construction. I changed the magnet lengths on both models and added my coil recipes. Now it was time to put it all into production.

By November of 1974, I was producing Super Distortions, Dual Sounds, Fat Strats and the Pre BS Tele all made with my own improved parts. (See September 1975 ad below on newsstands.) I started getting calls from guitar builders like Neil Moser from BC Rich Guitars and Paul Hamer from Hamer Guitars. Both said they were hearing great things about my pickups and wanted to use them in their guitars. I quickly realized that we were the “rebel alliance” all wanting the same thing: better guitars.

You can see one of my original Fat Strat pickups in the neck position of Van Halen’s Frankenstein guitar. The first year production were all made with the reddish brown Lamitex. I eventually found black Lamitex sheets and switched over the following year.

The Gibson EBO was the worst sounding bass pickup that I’d ever heard - a complete mud ball. My design directly size replaced it and I added the string tone and high end that the original design lacked. I also included a switch for series parallel wiring and it can be seen on Gene Simmons’ Spector bass from the early 70s. I was on a roll and had even more new designs on the way.

Steve Kaufman introduced me to Louie Gaudiosi (KLN Printing), and we designed our first one sixth and half page black and white ads for Guitar Player magazine. The new sixth of a page ad came out in the June 1975 issue and the half page in the August issue. Both were on the newsstand about two months before the cover date and design and insertion orders were about three months before that.

Sales continued to steadily increase, and Steve Kaufman suggested that we go to our first NAMM show in Chicago. I had no idea what a NAMM show was.